Story and Illustrations by

Sjirk de Boer.

Translation by

Frank de Boer.

Copyright © 1993 by

Frank de Boer.

Published by

Frank de Boer,

Waterloo, Ontario,

Canada.

Printed in Canada

How it started.

Only a few people know this story. The Locherfamily and our family will

remember it. My brother Herre and I have told the story to some of the

classes we had in our years as teachers. In Canada, my brother Frank

has told it to groups and packs of the boy scouts, when he was a leader

in that organization. Otherwise it's unknown. Let us try not to forget

it. In the deBoer family home it happened. This is a story about making

difficult decisions, about acts of hate and daring acts of compassion.

It happened around fifty years ago and exact dates may be forgotten,

some events may not be remembered in the right sequence. Fifty years

later I am starting to write the story. I am writing this for the

memory of our brave parents, for our children and grandchildren, our

grandchildren's friends and for future generations. Let it not yet be

forgotten.

On Friday, May 10 1940, the

German army started their invasion of Holland. At that time most people

in our small city of Sneek (pronounce Snake), believed that the German

forces would be beaten back by the Dutch army. This did not happen. The

next day German armored vehicles stopped in our street, right in front

of our house. We had just finished our Saturday noon dinner and I

clearly remember the dessert. Rice pudding with raisins, sprinkled with

sugar and with melted butter. Normally we finished dinner with a bowl

of buttermilk-barley-porridge.

Mother stood in front of a window

in our living room when the Germans stopped. She turned around and

promised us that we would have rice pudding for dessert on the day the

Germans left. Mother kept her promise.

Even when food became very scarce during the five war years, mother

saved some rice. On April 15, 1945, Canadian tanks stopped in front of

our house, in exactly the same spot where the Germans stood in 1940.

The next day mother served rice pudding for dessert. We did not get as

much as in 1940 and without raisins, sugar or melted butter. There was

another promise kept when the Canadian army arrived. The curtains

hanging in front of the living room windows opened again. Mother had

closed them when the German army vehicles stood in front of our house

in 1940. "They," she said, pointing at the German soldiers "do not have

to know what happens in our home".

After the Germans took control of the government, things started to

change in Holland. In the next street, two blocks down, lived Mr. Pino.

He had a corner store where you bought candies, chocolates, cigarettes,

and similar items. The Pino store closed on Saturdays, not on Sundays.

Most stores closed on Sundays. If needed people could buy cigarettes,

or bread on Sundays at Pino's. Saturday was Sabbath and that's why the

store closed on that day. The Pino family were Jews. When the German

army had been in Sneek for a few weeks, a small group of soldiers

walked past the Pino corner store. One of the soldiers noticed that Mr.

Pino was a Jew and he shouted: "Ein Jude, ein Jude und der Jude hat ein

Geschäft" (A Jew, a Jew and that Jew has a store). He pulled a hand

grenade from his boot, one with a long wooden handle, and was going to

throw this through the store window. The other soldiers stopped him.

The soldier's action really shocked the town; for days it was talked

about and it threw a real scare on the people.

In Sneek lived Jewish families who had left Hitler's Germany a few

years ago. My sister had worked for some of them as a seamstress; they

did not talk much, but a few things had been mentioned. We had heard

some of the stories how the Germans disliked Jews. The hand grenade

incident was the first experience for Sneek, and it showed a lot more

than only dislike.

Now the story.

The Locher family lived in Amsterdam. They were Jews.

Abraham and Sarah Locher and three children. Esther was the oldest,

followed by two boys, Jacob and Louis. Louis was the youngest, Looky,

they called him.

Mr. Locher owned a

fish store on a busy Street.The Locher family home was a few streets

away; they lived upstairs. With his delivery truck, very early each

morning, Mr. Locher drove to IJmuiden, a small harbor town on the North

Sea. Here he bought fish directly from the fishermen when they docked

with their overnight catch. He trucked the fish to his store in

Amsterdam. The couple worked the whole day in the store, sorting and

cleaning fish. Their clients always got fresh fish, and the store was

busy. The family enjoyed a good income from their business.

Mrs. Locher did not get much time to do any work at home. They had

hired a housekeeper for all the things that, fifty years ago normally a

housewife and mother would do. Mrs. Locher liked it better this way;

cooking, cleaning and doing the laundry, were not her strong points.

A major change happened when the Lochers received an official document

from the German controlled government.This document informed them that

they could no longer keep their store, or even work in it. The German

authorities took the store away and gave it to a collaborator.

The Lochers did not receive anything in return for their store.

According to the Germans, not any Jew was fit to run a business and no

Jew deserved compensation for confiscated property either.

Life for Jews got harder and harder. Many more rules and restrictions

came. A yellow star had to be worn on all outer clothing. It had to be

clearly visible and of a certain size. Everybody over a certain age had

to have an Identification Card. This ID card showed a photo,

fingerprints, address, name, etc., of the bearer. Cards issued to Jews

came with a big J printed on it. No longer could Jews go to any public

place. Coffee shops, restaurants, playgrounds, parks, swimming pools,

buses, trains, trams, were out of bounds to Jews. Shopping was limited

to a few hours and only on selected days. Jewish children were not

allowed to go to their own schools. They were sent to special German

controlled schools.

Slowly the situation got worse all across the country. Most foods were

rationed. Any item normally imported or manufactured from imported raw

materials became scarce or had completely disappeared from store

shelves. For example, the racks and shelves for tires and inner tubes

for bicycles, Holland's standard mode of transportation were empty.

Even with the necessary coupons you could not buy any. Clothing was

hard to get You were lucky if you found a shoemaker who had leather

left to resole your shoes. It helped if you had some bacon or butter to

barter with. Some of the scarce items could be bought on the emerging

black-markets, if you had the money.

Still, the general expectation was that Germany would soon start losing

the battles against the Allied forces and that the occupation would

come to an end. Resistance against German rule was hardly noticeable.

Generally, their orders were followed. The people knew that German

authorities expected total obedience. The population in Holland was

made aware of German ruthlessness and the severity of their

punishments. More and more the country started to find this out the

hard way.

For Jewish citizens the situation was a lot worse. Little did they know

what to expect next. Only a few people in Holland, Jew or not, had any

idea of Germany's intentions.

During 1942, letters

weresent to all Jews instructing them to appear, with hand luggage

only, at certain locations. In the letter they were told that, after

registration, they would be moved to camps in Germany to work in nearby

factories. Men and women were needed for this work, children had to

come along and could not be left behind.

A few Jews did not follow instructions and did not show up at their

appointed time and location. They disappeared, "dove under," as the

Dutch would say. Most of the Jewish "under-divers" got help from non

Jewish friends to stay out of German hands. The German- and the Dutch

police hunted these fugitives. When caught, the Germans took them

directly to Mauthausen.Similartreatment awaited people who helped Jews

escape from the Germans and got caught doing it, Mauthausen was a camp

built exclusively for punishment.

"Oh," Mr. Locher had remarked when they discussed the situation in the

Jewish community in Amsterdam, "my wife and I are used to working hard.

We don't mind long days. It may not be easy, but we will manage. We'll

see what happens. Nobody knows for sure."

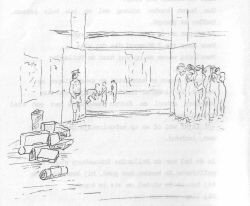

The Lochers also got the letter. It informed them to be at a well-known

theatre, the "Hollandse Schouwburg," for registration. During the past

few weeks some of the Locher's friends and relatives had already left.

Now it was officially their turn. Now they knew the date and time and

that they could take only a small suitcase or handbag each.

The family knew about working in the German factories and how the city

tram took everybody to Amsterdam's main train station, Central Station.

From here a train left every night for Drente, one of the Dutch

provinces bordering Germany. Close to the village of Westerbork there

was a camp where the Jews would be temporarily housed. Later a train

would come from Germany for them.

It was an early start for the whole family as they prepared for this

journey, there were clothes to be selected and suitcases to be packed.

Finally they were ready to go. A key was given to the neighbours, who

had promised to look after their home during their absence.

The Lochers pulled the front door closed behind them.

During the walk to the theatre they met several acquaintances. The boys

found friends from their old school, friends they had not seen for a

long time. Esther also met several old girlfriends. One of the girls

remarked that it looked as if they were going on a school trip, so many

of the old friends together with only hand luggage.

A Dutch policeman stood in the doorway to the lobby of the theatre.

They knew him well. For years he had been a regular customer in their

store. The policeman walked over to Mr. Locher and took him aside. "Mr.

Locher," he said, "listen to me, don't go inside, find an excuse and go

back. Don't trust the Germans. There is a great danger. You will be

killed if you go. Maybe, nobody will come back." Mr. Locher tried to

walk away, shaking his head, but the policeman blocked his way and

stood directly in front of him, whispering: "I will help you, my

friends and I will help you to dive under and stay out of the German

camps. I can give you ten minutes to make up your mind"

I can give you ten minutes to make up your mind!

Mr. and Mrs. Locher had ten minutes to decide on their future. What

course to take? What to believe, the letter they got, or the words from

the policeman they knew as a customer? In the meantime their two Sons

were playing outside with rediscovered friends and inside Esther also

seemed to have a great time with her old friends.

Occasionally you could hear Ester's voice clearly over the noise of the crowd.

Ten minutes later the eyes of the policeman and Mr. Locher met and he

nodded slightly. Mrs. Locher had taken Esther aside. She whispered in

her ear all they had heard from the policeman and told her about the

decision the parents had made. "Esther, go outside, where your brothers

are, leave your bag here," she urged her daughter. Esther's reaction

was different: "Oh Mom, you are again scared for no reason at all. We

girls have promised each other to stay together. What can happen? We'll

see what kind of work we will have to do. We are leaving!" Esther left

her mother and headed back to her circle of friends.

While Esther talked to her mother, her father went frantically through

his pockets and wallet as if he was searching for something important.

The policeman had been watching the family. He looked at the clock on

the far wall and slightly nodded.

Mr. Locher went over to him. "Sir," he said, "I must have forgotten my letter; it has

to be lying on the kitchen counter at home." The policeman shouted angrily, "Hurry up man, we don't have all day!"

The couple left the lobby, leaving all their luggage behind. One more inquiring look at Esther, who shook her head.

This was the last the parents ever saw of Esther, laughing with her friends, and shaking no with her head.

Once outside, the Lochers called Jacob and Louis and told them to leave

their suitcases lying with the luggage of their friends. The family,

only four now, took a different route back. On the way home the parents

told their sons about the changed plans.

Had it been a wise move? They had still time to go back to Esther.

Should they return to the theatre and rejoin their daughter, instead of

leaving her behind? These and a lot more questions raced through their

minds But the Lochers stayed at home Waiting, ... just waiting.

Towards evening the doorbell rang. The policeman, now in civilian

clothes, was standing outside. It felt like a relief when he took

charge. He told the Lochers, "first thing to do is to remove all the

yellow stars from your clothing. Secondly, make sure that with hard but

careful brushing none of the holes made by sewing remain visible in the

fabric. Next, put on as many layers of clothing as possible. Don't even

consider a suitcase but take only a small handbag or purse. Bring with

you as many as possible of your valuable items, like gold, silver,

jewelry and of course money." It was not an easy order to follow when

the policeman continued, "try not to look like fugitives and at the

same time carry as much clothing and valuables as possible".

Outside it was nearly dark, when the front door closed again behind

them. Their guide took the family through quiet streets for a long and

slow walk.The last part had been in almost total darkness because the

city was blacked out. Another German rule that allowed no street lights

to burn, no traffic lights to operate. No light shone through windows

of houses or stores either. Windows were covered with blackpaper, or

had some other way to keep the inside light from escaping. Finally they

reached their destination on the outskirts of the city. Here an area

was set aside by the city for gardeners. You could lease a small plot

of land to grow your own vegetables or flowers. Some people had leased

the same plots for years and they had built shacks in their gardens for

storage of garden tools and protection from rain and weather. In prewar

years, during a spell of hot weather, you could always find gardeners

spending the whole weekend at their gardens.

The Germans had

outlawed this. You could still work in your garden during daytime

hours, but could not spend the night in your shack. The Locher family

was taken to one of these shacks by their guide. Here, in totally

unfamiliar surroundings, they prepared for the first night away from

home, wondering how Esther and her friends made out.

That same night a train left the Central Station for Westerbork. Esther was one of the passengers.

The Locher family did not sleep much, this first night away from home.

They were city folk and had never before listened to rural night

sounds. The noise of ducks in the nearby ditches, the barking of a farm

dog in the distance, and the cry of the night heron kept them from a

sound sleep. Or did their new worries keep the sleep away?

The Lochers had started their wait for the end of the war. They learned

quickly that time seem to slow down when you are scared. No longer

could they reverse their first steps as fugitives. If caught by the

Germans, it would be a direct trip to Mauthausen. Wearing no yellow

star was enough for that. Their friend, the policeman, had told them

not to trust anybody, unless properly introduced. "Too many Dutch nazis

around", he said. "And don't forget the people who run to the Germans

for the thirty bucks they pay to anyone who betrays Jews in hiding!"

The shack did not give much room for moving around, somebody was

constantly in the way. The walls were just planking and far from being

soundproof. There could be no loud conversation and absolutely no

arguing. The Lochers knew nothing about the neighbours on the next

plot! There were no beds in the shack and only one bench, a few boards

hammered together. Bench is for Mom, the boys were told, we men can

sleep on the floor. They had enough blankets to stay warm overnight.

There was no toilet, but behind a curtain was a pail with a lid. On a

small counter stood another pail, this one had water in it and a ladle

for scooping hung on the rim. An old kerosene burner stood beside this

pail. It could be used for cooking or heating, but no kerosene had been

available for at least a year.

Every

day had one bright spot, a visitor. A woman, whose shack they stayed

in, came to work for a while in her garden. She would go inside to

stretch out and relax for an hour or so, when she got tired. At least,

this is what she told the other gardeners. In her bag she carried the

food and drink for the Lochers.

The underground, a name given to the combined actions of Dutch

civilians against the German occupation forces, had made all the

arrangements for the Lochers.

The underground informed the family that it had started the search for

more permanent hiding places for them. It had also mentioned that it

was better not to count on a place where the four could stay together.

It did not take long for the underground to find suitable spots for the

two boys. Jacob and Louis had to be ready one afternoon towards dusk

and a guide would come to take them away. A school bag was all they

could carry with them. Anything more would be too conspicuous.

After the departure of their sons, the Locher parents were alone in

their garden shack for some weeks. Till fall, when it became too cold

to be comfortable. It was a cold day when a contact person from the

underground came to tell the couple about possibilities. In the

northern part of Holland, in the province of Friesland, they located

several farmers who were willing to hide Jews. If the Lochers wanted,

the underground could make the arrangements to get them there. For sure

there would be more room and comfort at a farm than in a garden shack,

They had to realize that the trip would not be without danger. The

Lochers asked the underground to go ahead and start the plans for the

move. What other choice was there?

Several problems had to be solved first and a major one was

transportation. All the gasoline and diesel fuel available for buses

and cars had been consumed. Coal came from Limburg, one of the southern

provinces of Holland and was still available in limited quantities.

With that coal the train was the only way to travel any distance.

The Lochers would get new ID cards with real photos and fingerprints,

fake names and addresses and without the letter J this time. Train

tickets would be bought for them so they would not have to stand in

line at the station and risk being recognized and taken by German

police. The underground would look after all arrangements. Everything

had to be done with extreme caution.

The couple got a note with the details. They had to learn their new

names and birth dates, their new address and the address of the fake

family in Friesland they were supposedly going to visit. It also

informed them about the trip. All of this and how to recognize their

new underground contact had to be known by heart.

First they had to take the train to Zwolle, and there transfer to the

one for Leeuwarden, the provincial capital of Friesland. Heerenveen was

the next stop. Here the Locher couple was to walk from the train

station to the tram station next door and take the tram for Harlingen.

They read that this tram was not like an Amsterdam city tram, but more

like a train on a smaller scale. The tram tickets even looked a lot

like the train tickets. Their final stop would be at the tram station

in the city of Sneek. In Sneek the couple would meet the next

underground contact. The Lochers learned all this by heart, rehearsing

it again and again. They had to because in Zwolle the German police

routinely checked the ID cards of all the passengers on the train and

the Lochers could not afford to mix up any answers. When they were sure

that they knew everything, the note had to be totally destroyed.

The couple went on this dangerous journey.

In Zwolle, the German police did get on the train. The Lochers were

scared; a fear shared by all the other passengers in the compartment.

They thought that the police spent extra time on their ID.cards. Mrs.

Locher kept her eyes* down, but Mr. Locher had returned the German's

stare. Finally he had held his hand out and the police returned his ID.

Not a single word was spoken. A very scary moment has passed.

Finding the tram in Heerenveen was no problem. The people in their

compartment on the tram had looked at them, but had left the couple

alone. Nobody had talked to them or asked any questions. There was

something strange though, with their fellow passengers. The Lochers

found that they could not understand them! It sounded as if these

people, in Holland, talked a different language.

The tram stopped in a village called Joure. Some passengers got off and

a few more got on. About fifteen minutes later the tram entered a city

and the tracks ran between a canal and a street. At a bridge the tram

stopped. The couple was in doubt if this was the final destination and

then remembered that their instructions had clearly mentioned a station

and the Lochers stayed on. Only a few minutes later the tram stopped

again. Here a sign told them that this was indeed Sneek. A nearby

building looked like a station and the Lochers got their luggage out of

the overhead rack and stepped down on the platform. It was late

afternoon, almost dark. The other passengers disappeared quickly. The

couple waited on the platform. What would happen next?

End part 1